BOSTON, Mass. – Community Resources for Justice is rallying support to reverse the shrinking availability of services for men and women returning to Boston after serving time in prison or jail.

At a packed Nov. 2 meeting in the Bruce Bolling Municipal Building in Roxbury, CRJ gathered lawmakers, city and state officials, and community partners to highlight the reduction in reentry services for the 3,000 people who return to Boston each year after being incarcerated. The contraction in these services comes as Massachusetts considers significant criminal justice reform measures contained in multiple bills on Beacon Hill.

Former state Rep. Marie St. Fleur explains the lack of reentry resources in Boston.

“Reentry is critical,” said former state Rep. Marie St. Fleur, who facilitated the event. “Everyone says it’s important, but no one really wants to fund it. It can’t be done without resources.”

In the past year, programs and organizations offering case management, substance abuse services, and housing and supervision have closed or scaled back due to lack of funding. Span, Inc., closed in August. The Boston Reentry Initiative has been reduced. CRJ was forced to end the Overcoming the Odds case management program for Boston men with serious criminal records last fall, and will soon close McGrath House, a standalone program in the South End for women transitioning from incarceration back to the community.

CRJ’s Brooke House, a 65-bed prerelease program in the Fenway neighborhood, is now facing possible closure after a drop in funding. Over the last five years, the program served more than 1,100 men, primarily from the Suffolk County House of Corrections. Brooke House also serves clients through smaller contracts with the Massachusetts Parole Board, the Norfolk County Sheriff’s Office, and a new pilot program offering transitional housing.

Two graduates of Brooke House, Carlos and Prince, told the audience that the program helped them build a solid foundation to build on after finishing their sentences.

“Brooke House is a real cool program,” said Carlos, who began writing letters to CRJ at the beginning of his sentence in the hopes of landing a spot in the program. “I just wish it was expanded so more individuals could take part in these services.”

Prince, who spent nearly two decades behind bars beginning when he was 17, said Brooke House changed his life.

“I was basically lost,” he said. “I’m just here to support them because they helped me a lot on my journey in society.”

From March through August of this year, 85 percent of Brooke House clients successfully completed the program and 93 percent moved on to safe and stable housing. In August, 90 percent of clients were employed.

Laura van der Lugt, director of research and innovation in the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department, said loss of federal grants and increasing numbers of inmates with substance abuse problems and other complex needs have squeezed the department’s budget.

The opioid epidemic has increased the need for reentry services. Individuals recently released from prison are 120 times more likely to die of an overdose than the general population, especially in the first months after their release, according to the state Department of Public Health.

“A lot of people struggle in that transition,” CRJ President and CEO John Larivee said.

Massachusetts lags behind many other states in its investment in services that have been shown to reduce the likelihood that individuals released from jail or prison will be re-incarcerated for a conviction on new charges or parole or probation violations. More than two-thirds of people released from Massachusetts’ county jails and half of those released from state prisons in 2011 were re-arraigned within three years, according to research from the Council of State Governments.

Up-front investment in reentry also saves money in the long-term, advocates said. States like Alaska have included an infusion of cash into reentry programs as part of criminal justice reforms.

“It makes good fiscal sense,” said Dan Mulhern, director of Boston’s Office of Public Safety and a former Suffolk County prosecutor. “It’s a great investment in making sure our neighborhoods are safe and healthy.”

Reform bills before the Massachusetts Legislature currently do not designate funding for investment or reinvestment into reentry services.

State Sen. Will Brownsberger, D-Belmont, and state Reps. Russell Holmes, D-Boston, and Dan Cullinane, D-Boston, voiced their support during the meeting for reentry services.

“Investing in successful reentry programs overwhelming reduces recidivism,” Cullinane said. “It is that simple. Not only is it right thing to do on a human level, a policy level, and on a public safety level – investing in reentry programs like the Brooke House makes sure that the incredible financial cost of incarceration was not wasted, or worse will not have to be spent all over again. Collectively we need to do everything possible to ensure the continuation of this program and make sure it does not close due to lack of funding.”

Brownsberger, who sponsored a wide-ranging reform bill, said reentry programs need more solid funding that doesn’t get slashed when budgets get tight or grant opportunities dry up.

“I’m deeply troubled with where we are,” he said. “I look forward to working with my partners in the Legislature to try to give these types of programs funding that’s not as vulnerable to that kind of squeeze.”

Holmes urged supporters of reentry services to contact their lawmaker and advocate for criminal justice reform.

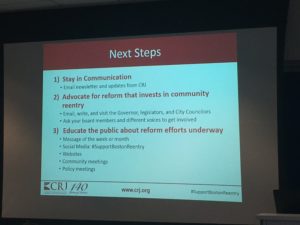

Next steps for supporting efforts to preserve existing programs like Brooke House and expand reentry services in Boston.