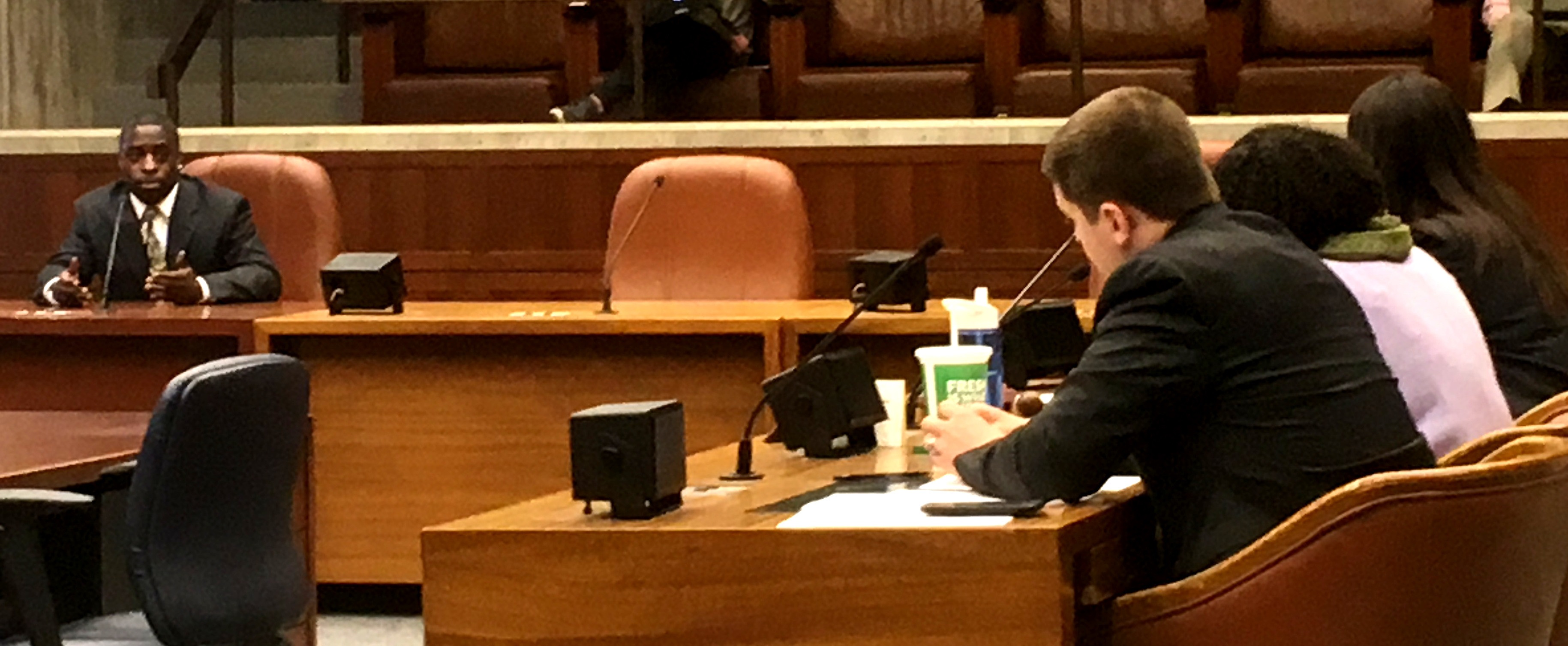

CAPTION: Boston City Councilors heard testimony on April 3, 2017, from (left to right) CRJ President and CEO John Larivee; Frank DeLuca, SCA reentry coordinator for the Boston Police Department; Massachusetts Department of Correction Assistant Deputy Commissioner Chris Mitchell; Gabriella Priest, interim deputy director of CRJ's Social Justice Services division; and True-see Allah, assistant deputy superintendent of reintegration services for the Suffolk County Sheriff's Department.

BOSTON — Coming up on the end of his state prison sentence last year, Ruark Bond decided his latest stretch behind bars would be his last.

At 39 years old, the self-described “repeat offender” had noticed that as his criminal record grew longer, so too did the length of his sentences. But making a fresh start after returning home to South Boston never seemed to get easier. He needed to make a change.

Now coming up on a year since his release in May of 2016, Bond said he’s turned his life around and is hoping that Community Resources for Justice will find new funding to restore the Overcoming the Odds program, which he says made that transition possible.

“Life is too important to be spending it behind the wall,” he told Boston city councilors during a hearing on the program Monday.

Overcoming the Odds began in 2013 as a partnership between CRJ, the Boston Police Department, and the Massachusetts Department of Correction. After assisting more than 280 men returning from state prison to Boston neighborhoods and developing a track record of reducing the likelihood that participants will be re-incarcerated, the program lost its federal funding in October of 2016.

CRJ is seeking $250,000 in new funding, which would allow 100 additional men to go through OTO.

The program was designed to work with men who were assessed as having a moderate or high risk of re-offending and who had significant criminal records, often related to drugs, guns, or gangs. The program worked with men before and after their release to help them find housing, steady jobs, vocational training, and substance abuse and mental health counseling services.

Frank DeLuca, reentry coordinator for the Boston Police Department’s Office of Research and Development, said OTO offers an alternative lifestyle to men who have had few options.

“I would hope we can find some source of funding for this program,” he said. “It’s heartbreaking.”

Representatives from CRJ, the Department of Correction and the Boston Police presented members of the city council’s Committee on Public Safety and Criminal Justice with data suggesting that the men who’ve gone through the program are significantly less likely to be charged with a new offense than those who have not.

Among the 281 men considered a moderate or high risk to re-offend who have completed the program, 14 percent have been re-incarcerated. By comparison, the rate at which all men considered low, moderate, or high risk returning to Boston neighborhoods from Massachusetts prisons are re-incarcerated within three years is 33 percent.

OTO graduate Ruark Bond testifies before Boston city councilors on April 3, 2017.

Men in prison who were invited to the program in its early days first viewed it with suspicion. But CRJ President and CEO John Larivee said OTO has gained credibility on both sides of prison walls for helping returning men navigate an often disconnected array of services, all the way from getting a bus pass to get to work to creating a resume for the first time.

“The goal was to get individuals engaged and participating. That, we thought, was the secret to enhanced public safety,” Larivee said. “It wasn’t to supervise them more closely or more frequently. It was to get them engaged with case managers and the services that can be provided both by the public entities and the private agencies.”

Gabriella Priest, deputy director of CRJ’s Social Justice Services division, said OTO was based on extensive research shown to reduce recidivism. The program relied on individual case plans for each participant, employing a mix of encouragement, goal setting, and accountability to keep them on track.

“Positive reinforcement is something our case managers are trained on,” she said. “We know that that carrot works. We know that when individuals are told they’re doing something well, that they’re encouraged to keep doing that.”

City Councilor Andrea Campbell, who heads the council’s Committee on Public Safety and Criminal Justice, said OTO has a “proven record of success” and a solid reputation with social service agencies and participants.

“You guys built that trust,” she said. “The question is: How can the City of Boston support you to keep this going?”

Bond, dressed in a charcoal pinstriped suit he acquired with help from his OTO case manager, said the support and positive reinforcement he received helped him get a good job at a UPS shipping center and held him accountable for meeting his goals for rebuilding his life. He said the program can help many more men achieve similar success.

“We do it basically because at the end of the day we need help,” he said of incarcerated men who enrolled in OTO. “It’s very hard coming back. You don’t want to be 39 and have no options.”